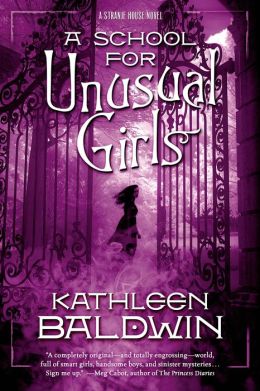

A School for Unusual Girls

Pub: May 19, 2015

Pre-OrderIt’s 1814. Napoleon is exiled on Elba. Europe is in shambles. Britain is at war on four fronts. And Stranje House, a School for Unusual Girls, has become one of Regency England’s dark little secrets. The daughters of the beau monde who don’t fit high society’s constrictive mold are banished to Stranje House to be reformed into marriageable young ladies. Or so their parents think. In truth, Headmistress Emma Stranje, the original unusual girl, has plans for the young ladies—plans that entangle the girls in the dangerous world of spies, diplomacy, and war.

Excerpt

The headmistress, Miss Emma Stranje, sat behind her desk, mute, assessing me with unsettling hawk eyes. In the flickering light of the oil lamp, I couldn’t tell her age. She looked youthful one minute, and ancient the next. She might’ve been pretty once, if it weren’t for her shrewd measuring expression. She’d pulled her wavy brown hair back into a severe chignon knot, but stray wisps escaped their moorings giving her a feral cat-like appearance.

I tried not to cower under her predatory gaze. If this woman intended to be my jailer, I needed to stand my ground now or I would never fight my way out from under her thumb.

My mother cleared her throat and started in, “You know why we are here. As we explained in our letters—”

“It was an accident!” I blurted and immediately regretted it. The words sounded defensive, not strong and reasoned as I had intended.

Mother pinched her lips and sat perfectly straight, primly picking lint off her gloves as if my outburst caused the bothersome flecks to appear. She sighed. I could almost hear her oft repeated complaint, ‘why is Georgiana not the meek biddable daughter I deserve.’

Miss Stranje arched one imperious eyebrow, silently demanding the rest of the explanation, waiting, unnerving me with every tick of the clock. My mind turned to mush. How much explanation should I give? If I told her the plain truth she’d know too much about my unacceptable pursuits. If I said too little I’d sound like an arsonist. In the ensuing silence, she tapped one slender finger against the dark walnut of her desk. The sound echoed through the room—a magistrate’s gavel, consigning me to life in her prison. “You accidentally set fire to your father’s stables?”

My father growled low in his throat and shifted angrily on the delicate Hepplewhite chair.

“Yes,” I mumbled, knowing the fire wasn’t the whole reason I was here, merely the final straw, a razor sharp spear-like straw. Unfortunately, there were several dozen pointy spears in my parents’ quiver of what’s-wrong-with-Georgiana.

If only they understood. If only the world cared about something beyond my ability to pour tea and walk with a mincing step. I decided to tell Miss Stranje at least part of the truth. “It was a scientific experiment gone awry. Had I been successful—”

“Successful?” roared my father. He twisted on the flimsy chair putting considerable stress on the rear legs as he leaned in my direction, numbering my sins on his fingers. “You nearly roasted my prize hunters alive! Every last horse — scared senseless. Burned the bleedin’ stables to the ground. To the ground! Nothing left but a heap of charred stone. Our house and fields would’ve gone up next if the tenants and neighbors hadn’t come running to help. That ruddy blaze would’ve taken their homes and crops, too. Successful? You almost reduced half of High Cross Greene to ash.”

Every word a lashing, I nodded and kept my face to the floor, knowing he wasn’t done.

“As it was, you scorched more than half of Squire Thurgood’s apple orchard. I’ll be paying dearly for those lost apples over the next three years, I can tell you that. And what about my hounds!” He paused for breath and clamped his teeth together so tight that veins bulged at his temples and his whole head trembled with repressed rage.

In that short fitful silence, I could not help but remember the sound of those dogs baying and whimpering, and the faces of our servants and neighbors smeared with ash as we all struggled to contain the fire, their expressions—grim, angry, wishing me to perdition.

“My kennels are ruined. Blacker and smokier than Satan’s chimney…” He lowered his voice, no longer clarifying for Miss Stranje’s sake, and spit one final damning indictment into my face. “You almost killed my hounds!” He dismissed me with an angry wave of his hand. “Successful. Bah!”

My stomach churned and twisted with regret. Accident. It was an accident. I wished he had slapped me. It would’ve stung less than his disgust.

I wanted to point out the merits of inventing a new kind of undetectable invisible ink. If such an ink had been available, my brother might still be alive. As it was, the French intercepted a British courier and Robert’s company found themselves caught in an ambush. It wouldn’t help to say it. I tried the day after the fire and Father only got angrier. He’d shouted obscenities, called me a foolish girl, “It’s done. Over. He’s gone.”

Nor would it help to remind him that I’d nearly died leading the horses out of the mews. His mind was made up. Unlike my father’s precious livestock, my goose was well and truly cooked. He intended to banish me, imprison me here at Stranje House just as Napoleon was banished to Elba.

Miss Stranje glanced down at my mother letter. “It says here, that on another occasion Georgiana jumped out of an attic window?”

“I didn’t jump. Not exactly.”

“She did.” Father crossed his arms.

It had happened two and a half years ago. One would’ve thought they’d have forgotten it by now. “Another experiment,” I admitted. “I’d read a treatise about DaVinci and his—”

“Wings.” My mother cut me off and rolled her eyes upward to contemplate the ceiling. She employed the same mocking tone she always used when referring to that particular incident.

“Not wings,” I defended, my voice a bit too high pitched. “A glider. A kite.”

Mother ignored me and stated her case to Miss Stranje without any inflection whatsoever. “She’s a menace. Dangerous to herself and others.”

“I took precautions.” I forced my voice into a calmer, less ear-bruising range, and tried to explain. “I had the stable lads position a wagon of hay beneath the window.”

“Yes!” Father clapped his hands together as if he’d caught a fly in them. “But you missed the infernal wagon, didn’t you?”

“Because the experiment worked.”

“Hardly.” With a scornful grunt he explained to Miss Stranje, “Crashed into a Sycamore tree. Wore her arm in a sling for months.”

“Yes, but if I’d made the kite wider and taken off from the roof—”

“This is all your doing.” My father shot a familiar barb at my mother. “You never should’ve allowed her to read all that scientific nonsense.”

“I had nothing to do with it,” she bristled. “That bluestocking governess is to blame.”

Miss Grissmore. An excellent tutor. A woman of outstanding patience, the only governess in ten years able to endure my incessant questions, sent packing because of my foolhardy leap. I glared at my mother’s back remembering how I’d begged and explained over and over that Miss Grissmore had nothing to do with it.

“I let the woman go as soon as I realized what she was.” Mother ignored Father’s grumbled commentary on bluestockings and demanded of Miss Stranje, “Well? Can you reform Georgiana or not?”