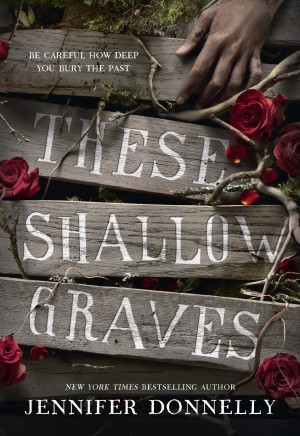

These Shallow Graves

Pub: October 27, 2015

Delacorte Press Books for Young Readers

Pre-OrderFrom Jennifer Donnelly, the critically acclaimed New York Times bestselling author of A Northern Light and Revolution, comes a mystery about dark secrets, dirty truths, and the lengths to which people will go for love and revenge. For fans of Elizabeth George and Libba Bray, These Shallow Graves is the story of how much a young woman is willing to risk and lose in order to find the truth.

Darkbriar Asylum for the Insane

New York City

November 29, 1890

Josephine Montfort stared at the newly mounded grave in front of her and at the wooden cross marking it.

“This is the one you’re after. Kinch,” Flynn, the gravedigger, said, pointing at the name painted on the cross. “He died on Tuesday.”

Tuesday, Jo thought. Four days ago. Time enough for the rot to start. And the stink.

“I’ll be wanting my money now,” Flynn said.

Jo put her lantern down. She fumbled notes out of her coat pocket and counted them into Flynn’s hand.

“You get caught out here, you never saw me. You hear, girl?”

Jo nodded. Flynn pocketed his money and walked off into the darkness. Moonlight spilled over the rows of graves and over the looming towers of the asylum. A wail rose on the night, thin and chilling.

And suddenly Jo’s courage failed her.

“Step aside, Jo. We’ll do it. Oscar and me,” Eddie said.

He was standing across from her, on the other side of the grave. He said nothing more as she met his gaze. He didn’t have to. The challenge in his eyes spoke volumes.

How did this happen? How did I get here? Jo asked herself. She didn’t want to do this. She wanted to be home. Safe inside her Gramercy Square brownstone. She wished she’d never met Eddie Gallagher. The Tailor. Madam Esther. Fairy Fay. Most of all, she wished she’d never laid eyes on the man buried six feet below her.

“Wait by the vault. Go back,” Eddie said. Not unkindly.

Jo laughed. Go back? How? There was no going back. Not to her old life of drawing rooms and dances. Not to Miss Sparkwell’s School. Not to her friends, or to Bram. It had all gone too far.

“Jo . . .”

“You wait by the vault, Eddie,” Jo said crisply.

Eddie snorted. He tossed a shovel at her. Jo flinched as she caught it, then started to dig.

Chapter One

Miss Sparkwell’s School for Young Ladies

Farmington, Connecticut

September 17, 1890

“Trudy, be a dear and read these stories for me,” said Jo Montfort, laying out articles for her school’s newspaper on a tea table. “I can’t abide errors.”

Gertrude Van Eyck, all blond curls and dimples, stopped dead in the middle of the common room. “How did you know it was me? You didn’t even look up!”

“Duke told me,” Jo replied. Duke’s Cameos were Trudy’s favorite brand of cigarette.

Trudy sniffed her sleeve. “Do I smell?”

“You positively reek. What does Gilbert Grosvenor think of you smoking cigarettes?”

“Gilbert Grosvenor doesn’t know. Not about the ciggies, or the bottle of gin under my bed, or that utterly swell boy who delivers apples,” Trudy said, winking.

“Slang does not become a Farmington girl, Gertrude,” sniffed Libba Newland, seated nearby with her friend, May Delano.

“Neither does that fringe, Lib,” said Trudy, eyeing Libba’s badly curled bangs.

“Well, I never!” Libba huffed.

“And I’m sure you never will,” Trudy said archly.

“Stop being awful and read these, Tru,” Jo scolded. “My deadline’s tomorrow.”

Trudy sat down at the table and helped herself to a jam tart from Jo’s plate. It was three o’clock—teatime at Miss Sparkwell’s—and the common room was crowded with students on break. Everyone was chatting and eating except Jo, who was busy finalizing the layout for the second edition of the Jonquil.

“What do we have this week?” Trudy asked. “The usual tripe?”

Jo sighed. “I’m afraid so,” she said. “There’s a piece on the proper way to brew tea, a poem about kittens, Miss Sparkwell’s impressions of the Louvre, and advice on how to fade freckles.”

“Ye gads. Anything else?”

Jo hesitated, working up her nerve. “As a matter of fact, yes. A story on the abuse of girl laborers at Fenton’s Textile Mill,” she said, handing one of the articles to her friend.

“Ha! So funny, my darling!” Trudy said, smiling. Her smile faded as she read the first lines. “Oh dear God. You’re serious.”

Trudy kept reading, riveted, and Jo watched her, thrilled. Jo was a senior at Miss Sparkwell’s and had written for the Jonquil during her three previous years at the school, but this was the first important story she’d written. She’d worked hard to get it. She’d taken risks. Just like a real reporter.

“What do you think?” she asked eagerly when Trudy finished reading.

“I think you’ve lost your mind,” Trudy replied.

“But do you think it’s good?” Jo pressed.

“Very.”

Jo, who’d been perched on the edge of her seat, shot forward and hugged Trudy, a huge grin on her face.

“But that’s entirely beside the point,” Trudy said sternly as Jo sat down again. “If you hand in the layout to Sparky with that story in it, you’re done for. Detention for a week and a letter home.”

“It’s not that bad. Nellie Bly’s pieces are far more provocative,” said Jo.

“You’re comparing yourself to Nellie Bly?” Trudy asked, incredulous. “Need I remind you that she’s a scandalous lady reporter who meddles in other people’s business and has no hope of marrying a decent man? You, in contrast, are a Montfort, and Montforts marry. Early and well. And that is all.”

“Well, this Montfort’s going to do a bit more,” Jo declared. “Like write stories for newspapers.”

Trudy raised a perfectly arched eyebrow. “Is that so? Have you informed your mother?”

“Actually, no. Not yet,” Jo admitted.

Trudy laughed. “Not ever, you mean. Unless you want to find yourself locked away in a convent until you’re fifty.”

“Tru, this is a story that must be told,” Jo said, her passion clear in her voice. “Those poor girls are being mistreated. They’re worked hard and paid little. They’re practically slaves.”

“Jo. How on earth do you know this?”

“I spoke with some of them.”

“You didn’t,” Trudy said.

“I did. On Sunday. After services.”

“But you went straight to your room after services. You said you had a headache.”

“And then I climbed out of my window and went down to the river. To one of the boardinghouses there,” Jo said, lowering her voice. She didn’t want anyone to overhear her. “A farmer gave me a ride in his wagon. I spoke with three girls. One was seventeen. Our age, Tru. The others were younger. They work ten-hour days standing at these hellish looms. Injuries are common. So is exposure to coarse language and . . . and situations. I was told that some of the girls fall in with bad sorts and become wayward.”

Trudy’s eyes widened. “Josephine Montfort. Do you really think that Mr. Abraham Aldrich wants his future wife to even know that wayward girls exist, much less write about them? The future Mrs. Aldrich must be pure in mind as well as body. Only men are supposed to know about”—Trudy lowered her voice, too—“about sex. If news of what you’ve done gets around, not only will you lose your place here, you’ll lose the most eligible bachelor in New York. For goodness’ sake, be sensible! No mill girl, wayward or otherwise, is worth the Aldrich millions!”

May Delano looked up from her book. “What’s a wayward girl?” she asked.

Jo groaned.

“Never mind,” Trudy said.

“Tell me,” May whined.

“Very well,” Trudy replied, turning to look at May. “A girl who is with child but without a husband.”

May laughed. “Shows what you know, Trudy Van Eyck. The stork brings babies after you’re married, not before.”

“Come, May, we’re leaving” said Libba Newland, shooting Trudy a dirty look. “The common room is getting a bit too common.”

“I’ll bet you a dollar Lib tattles to Sparky,” Trudy said darkly, watching them go. “I just finished my detention for smoking. Now you’ve earned me some more!”

Disappointed by Trudy’s lack of enthusiasm for her story, Jo snatched it back. She wished Trudy understood her. Wished someone did. She’d read Bly’s Ten Days in a Mad-House and Jacob Riis’s How the Other Half Lives, and they’d touched her deeply. She’d been appalled to learn how the poor suffered and felt compelled to follow the examples those two reporters set, if only in some small way.

She thought about the mill girls she’d spoken with. They’d looked so crushingly tired. Their faces were as pale as milk, except for the dark smudges under their eyes. They’d been taken out of school and made to work. They weren’t allowed to talk or to go to the bathroom until their lunch breaks. One told her she could barely walk home at the end of the day, her legs hurt so badly from standing.

Their stories had made Jo sad—and blisteringly angry. “Trudy, why did I become editor of the Jonquil?” she suddenly asked.

“I have no idea,” Trudy replied. “You should’ve joined the glee club. Even you can’t get into trouble singing ‘Come into the Garden, Maud.’”

“I shall tell you.”

“I had a feeling you would,” Trudy said dryly.

“I did it because I want to inform my readers. Because I wish to draw back the veil that hides the injustices that surround us,” Jo said, her voice rising. “We who have means and a voice must use them to help those who have neither. Yet how can we help them if we don’t even know about them? And how can we know about them if no one writes about them? Is it so wrong to want to know things?”

Heads turned as Jo finished speaking. Girls stared. She glared back at them until they turned away. “They suffer, those mill girls,” she said, her voice quieter, but her heart still full of emotion. “They are so terribly unfortunate.”

Trudy took her hand. “My darling Jo, there is no one more unfortunate than we ourselves,” she said. “We are not engaged yet, you and I. We’re spinsters. Pathetic nobodies. We can go nowhere on our own. We must not be too forward in speech, dress, or emotion lest we put off a potential suitor. We are allowed no funds of our own, and most of all”—she squeezed Jo’s hand for emphasis—“no opinions.”

“Doesn’t it bother you, Tru?” Jo asked, frustrated.

“Of course it does! Which is why I intend to marry as soon as I can,” Trudy said.

She jumped up, snapped open an imaginary fan, and strode about the room imitating a society lady. “When I am Mrs. Gilbert Grosvenor and happily installed in my grand Fifth Avenue mansion, I shall do exactly as I please. I shall say what I like, read what I like, and go out every evening in silks and diamonds to smile at my beaux from my box at the Met.”

It was Jo’s turn to raise an eyebrow. “And Mr. Gilbert Grosvenor? Where will he be?” she asked.

“At home. Sulking by the fire with a copy of The Wall Street Journal,” Trudy said, imitating Gilbert’s eternally disapproving expression.

Jo laughed despite herself. “I’ll never understand how you were passed over for the lead in the school play. You belong on stage,” she said.

“I wasn’t passed over, thank you. I was offered the lead and declined it. Mr. Gilbert Grosvenor frowns upon theatricals.”

For a moment, Jo forgot about her own worries. She knew Gilbert. He was smug and disapproving, an old man at twenty. He was also stinking rich.

“Will you really marry him?” she asked. She could no more see beautiful, lively Trudy married to Gilbert than she could picture a hummingbird paired with a toad.

“I mean to. Why shouldn’t I?”

“Because you . . . You’ll have to . . .” She couldn’t say it.

“Go to bed with him?” Trudy finished.

Jo blushed. “That is not what I was going to say!”

“But it’s what you meant.”

Trudy looked out of a nearby window. Her eyes traveled over the lawns to the meadows, then farther still, to a place—a future—only she could see.

“A bit of nightly unpleasantness in exchange for days of ease. Not such a bad bargain,” Trudy said, with a rueful smile. “Some of us are not as well off as others. My papa can barely manage my school fees, never mind the dressmaker’s notes. And anyway, it’s not me I’m worried about. It’s you.” Trudy turned her attention back to Jo. “You know the rules: get yourself hitched, then do what you like. But for heaven’s sake, until you get the man, smile like a dolt and talk about tulips, not mill girls!”

Jo knew Trudy was right. Sparky would be appalled if she ever found out what Jo had done. So would her parents, the Aldriches, and the rest of New York. Her New York, at least—old New York. Well-bred girls from old families came out, got engaged, and then went back—back to drawing rooms, dinner parties, and dances. They did not venture into the dangerous, dirty world to become reporters, or anything else.

The boys got to, though. They couldn’t become reporters either—that was too grubby an occupation for a gentleman—but they could own a newspaper, run a business, practice law, breed horses, have agricultural interests, or do something in government like the Jays and the Roosevelts. Jo knew this but couldn’t accept it. It chafed at her spirit, as surely as the stays of her corset chafed her body.

Why is it, she wondered now, that boys get to do things and be things, and girls only get to watch?

“Jo?”

Jo looked up. It was Arabella Paulding, a classmate.

“Sparky wants to see you in her office,” she said. “Right away.”

“Why?” Jo asked.

“She didn’t say. She told me to find you and fetch you. I’ve found you, so go.”

“Libba tattled,” Trudy said ominously.

Jo gathered up her papers, dreading her interview with the headmistress. She was in for it.

“Don’t worry, my darling,” Trudy said. “You’ll only get a few days’ detention, I’m sure. Unless Sparky expels you.”

“You’re such a comfort,” said Jo.

Trudy smiled ruefully. “What can I say? I merely wish to smoke. Sparky can forgive that. You, on the other hand, wish to know things. And no one can forgive a girl for that.”

Chapter Two

Jo hurried out of Hollister Hall, crossed the grassy quad, and entered Slocum, where the headmistress’s office was. A tall gilt mirror stood in the foyer. It caught her image as she rushed by it—a slender girl wearing a long brown skirt, a pin-striped blouse, and lace-up boots. Wavy black hair formed a widow’s peak over a high forehead, and a pair of lively gray eyes stared out from an uncommonly pretty face.

“You’d be a beauty,” her mother often told her, “if only you’d stop scowling.”

“I’m not scowling, Mama, I’m thinking,” Jo always replied.

“Well, stop. It’s unappealing,” her mother would say.

Jo reached the door to Miss Sparkwell’s office and paused, steeling herself for a thorough dressing down. She knocked.

“Enter!” a voice called out.

Jo turned the knob and pushed the door open, prepared to see the headmistress wearing a grave expression. She was not prepared, however, to see her standing by a window dabbing at her eyes with a handkerchief. Had the mill girls story upset her that much?

“Miss Sparkwell, I don’t know what Libba said to you, but the story has merit,” Jo said, launching a preemptive strike. “It’s high time the Jonquil offered its readers something weightier than poems about kittens.”

“My dear, I did not summon you here to talk about the Jonquil.”

“You didn’t?” Jo said, surprised.

Miss Sparkwell passed a hand over her brow. “Mr. Aldrich, would you? I-I find I cannot,” she said, her voice catching.

Jo turned around and was astonished to see two of her oldest friends—Abraham Aldrich and his sister, Adelaide—seated on a divan. She’d been so preoccupied with defending her story, she hadn’t even noticed them.

“Bram! Addie!” she exclaimed, rushing to her friends. “What a lovely surprise! But I wish you’d have let me know you were coming. I would’ve changed out of my uniform. I would have . . .” Her words trailed off as she realized they were both dressed entirely in black. A cold dread gripped her.

“I’m afraid we have some bad news, Jo,” Bram said, rising.

“Oh, Jo. Be brave, my darling,” Addie whispered, joining him.

Jo looked from one to the other, her dread growing. “You’re frightening me,” she said. “For goodness’ sake, what is it?” And then she knew. Mr. Aldrich had been in poor health for some time. “Oh, no. Oh, Bram. Addie. It’s your father, isn’t it?”

“No, Jo, not ours,” said Addie quietly. She took Jo’s hand.

“Not yours? I—I don’t understand.”

“Jo, your father is dead,” Bram said. “It was an accident. He was cleaning a revolver in his study last night and it went off. Addie and I have come to fetch you home. We’ll get your things, and then . . .”

But Jo didn’t hear the rest. The room, and everything in it, whirled together then spun apart. For a few seconds, she couldn’t breathe or speak. How could her father be dead? Of the many sure and solid things in her life, he was the surest. And now Bram was telling her that he was gone . . . gone . . . and it felt like the world was crumbling under her feet.

“Jo? Can you hear me? Josephine, look at me,” Bram was by her side now. He’d put a steadying hand on her arm.

The sound of his voice pulled her back, reminding her that their sort did not make scenes in public. And public, to an Aldrich or a Montfort, was any place other than one’s own bedroom.

“Are you all right?” he asked her.

Jo managed to answer. “Yes, thank you,” she said. She forced herself to continue. “I shall be ready shortly. I just need to gather a few things. Please excuse me.”

“Let me come with you,” Addie said. She took Jo’s arm and led her out of the room. Together they headed for the dormitory. “We’ll try for the 5:05. It’ll get us to Grand Central before dark. We certainly don’t want to arrive after dark. It’s far too dangerous,” she fretted. “This city’s no longer fit for our kind. It’s been overrun by foreigners, criminals, and typists.”

Addie’s chatter barely registered. Jo was dazed, struggling to put one foot in front of the other. The quad with its lawns and buildings passed by in a blur. She’d walked this very same path only moments ago, but barely recognized it now. In the space of a heartbeat, everything had changed.

The dormitory was deserted when they reached it. All the other students were at clubs or in the library. Addie opened the door to Jo’s room and ushered her inside. “Here we are, all by ourselves. You can cry now if you need to and no one will see,” she said.

Jo sat down on her bed, frozen with shock. She waited for the storm of tears to come, but they didn’t.

Addie started to hunt for Jo’s valise, but Jo stopped her. “There’s no need to pack,” she said. “I’ve plenty of clothing at home. If you could just get my coat, gloves, and hat.”

“What a brave girl you are, holding back your tears,” Addie said. “It’s better that way, though. No red eyes at the station. No reason for the great unwashed to gawk.”

Jo nodded woodenly. Addie was wrong, but Jo didn’t correct her. She wasn’t holding her tears back; she had none. She desperately wanted to cry, but couldn’t.

It was as if her heart, corseted as tightly as her waist, could not find its shape again.