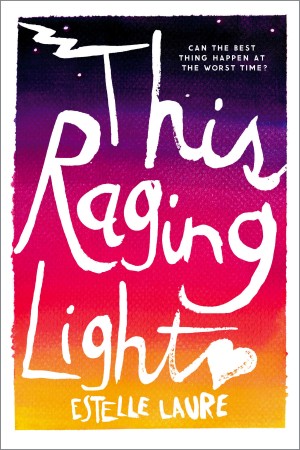

This Raging Light

Pub: December 22, 2015

HMH Books for Young Readers

Pre-OrderCan the best thing happen at the worst time?

Her dad went crazy. Her mom left town. She has bills to pay and a little sister to look after. Now is not the time for level-headed seventeen-year-old Lucille to fall in love. But love—messy, inconvenient love—is what she’s about to experience when she falls for Digby Jones, her best friend’s brother. With blazing longing that builds to a fever pitch, Estelle Laure’s soulful debut will keep readers hooked and hoping until the very last page.

Day 14

Mom was supposed to come home yesterday after her two-week vacation. Fourteen days. Said she needed a break from everything (See also: Us) and that she would be back before the first day of school. I kind of knew she wasn’t going to show up, on account of what I got in the mail yesterday, but I waited up all night just the same, hoping, hoping I was just being paranoid, that my pretty-muchnever-wrong gut had made some kind of horrible mistake. The door didn’t squeak, the floorboards never creaked, and I watched the sun rise against the wall, my all-the-way-insides knowing the truth: we are alone, Wrenny and me, at least for now. Wren and Lucille. Lucille and Wren. I will do whatever I have to. No one will ever pull us apart. That means keeping things as normal as possible. Faking it. Because things couldn’t be further from.

Normal got gone with Dad.

It gave me kind of a funny floating feeling as I brushed Wren’s hair into braids she said were way too tight, made coffee, breakfast, lunch for the two of us, got her clothes, her bag, walked her to her first day of fourth grade, saying hi to everyone in the neighborhood while I tried to dodge anyone who might have the stones to ask me where the hell my mother was. But I did it all wrong, see. Out of order.

I should make coffee and get myself ready first. Wren should get dressed after breakfast and not before, because she is such a sloppy eater. As of this morning, she apparently doesn’t like tuna (“It looks like puke-ick”), which was her favorite yesterday, and I only found out when it was already packed and we were supposed to be walking out the door. I did the piles of deflated laundry, folded mine, hung up Mom’s, carefully placed Wren’s into her dresser drawers, but it turns out none of her clothes fit right anymore. How did she grow like that in two measly weeks? Maybe because these fourteen days have been foreverlong.

These are all things Mom did while nobody noticed. I notice her now. I notice her isn’t. I notice her doesn’t. I want to poke at Wren, find out why she doesn’t ask where Mom is on the first day of school, why Mom isn’t here. Does she know somewhere inside that this was always going to happen, that the night the police came was the beginning and that this is only the necessary, inevitable conclusion?

Sometimes you just know a thing.

Anyway, I did everything Mom would do. At least, I tried to. But the universe knows good and well that I am playing at something, pretending from a manual I wish I had. Still, when I kissed the top of Wren’s dark, smooth head goodbye, she skipped into the school building. That’s got to count for something.

It’s a balmy morning. Summer doesn’t know it’s on the outs yet, and I quickstep the nine blocks between the schools. By the time I push through the high school doors, I am sweating all over the place.

And now I’m here. In class. The song Wren was singing on the way to school pounds a dull and boring headache through me, some poppy beat. I’m a little late to English, but so is mostly everyone else on the first day. Soon we’ll all know exactly where we’re supposed to be and when, where we sit. We’ll be good little sheople.

Eden is here, always on time, early enough to stake her claim to exactly the seat she wants, her arm draped over the back of an empty chair next to her, until she sees me and drops it to her side. English is the only class we got together this year, which is a ball of suck. First time ever. I like it better when we get to travel through the day side by side. At

least our lockers are next to each other’s.

She’s so cool, but in her totally Eden way. It’s not the kind of cool that says come and get me. It’s the kind that watches and waits and sees a lot — a thinking kind. Her thick, flaming hair virtually flows over the back of her chair, and her leather-jacket armor is on, which you would think is a little excessive for September in Cherryville, New Jersey, except for the fact that they blast the air conditioning at this school so it’s movie-theater cold, and really I’m wishing I had a jacket, wishing I had packed Wren something cozy in her backpack too, but I’m pretty sure it’s not quite so bad at the elementary school. I think the high school administration has decided that freezing us out might help control our unruly hormones or something.

They are wrong.

Mr. Liebowitz gives me a look as I sit down. I have so rudely interrupted his standard cranky speech about the year, about how he’ll take no guff from us this time around, about how just because we’re seniors doesn’t mean we get to act like jackasses and get a free pass. Or maybe he’s giving me that look because he knows about Dad, too. People titter all around me, but it’s like Eden and her leather jacket muffle all that noise right out. As long as I have her, I’m okay. I never mess around much with other people anyway. Digby may be her twin, but I’m the one she shares a brain with.

Meanwhile, Liebowitz looks like Mister Rogers, so he can growl and pace as much as he wants and it has no effect. You know he’s a total softie, that he can’t wait to get home and change into his cardigan and comfy shoes at night, so he can get busy taking superspectacular care of his plants and play them Frank Sinatra or something. He’ll calm down. He always starts the year uptight. Who can blame him? High school is a total insane asylum. They need bars on the windows, security guards outside. They would never do that here.

Eden kicks her foot into mine and knocks me back into now. I do not like now, and so I kick back, wondering if playing footsies with my best friend qualifies as guff.

“Dinner,” she mouths.

“Wren,” I mouth back. Shrug.

My eyes tell her about Mom without meaning to.

She shakes her head. Then, “Bitch,” she says in a whisper.

I shrug again, try to keep my eyes from hers.

“Bring Wren. My Mom will feed the world.”

I nod.

“Digby will be there.” She kicks my foot again.

I make my whole self very still. Stare at Liebowitz as his thin, whitish lips form words.

“Well, he does live at your house,” I say. Superlame.

“Ladies,” Liebowitz says, all sing-songy warning. “It’s only the first day. Don’t make me separate you.”

Good luck separating us, I want to say. Good luck with that.

Go feed your fish and water your plants. Get your cardigan and your

little sneakers on, and leave me alone.

It’s a beautiful day in the neighborhood. Won’t you be my

neighbor?

When Wrenny and I roll up the hill to Eden’s house in Mom’s ancient Corolla, Digby and his dad, John, are outside playing basketball, and I want to get in the house as fast as possible,

because otherwise I might be trapped here all day, staring. I get a little twinge of something seeing a dad and his kid playing ball like dads and kids are supposed to. That’s a real

thing, and my hand wants to cover Wren’s face so she can’t see all that she is missing.

Which reminds me. “Wren.”

“Yeah?” She’s wiping at her shirt, reading a book on her lap, and she’s a little bit filthy, her hair greasy and knotty in spite of my efforts this morning. At some point the braids came out, and she’s reverted to wild.

“You know how Mom hasn’t been around lately?”

She stops. Tightens. “Yeah,” she says.

“Well, we don’t want anyone to know about that, okay?

Even Janie and Eden and Digby and John.”

“But Mom’s on vacation. She’s getting her head together. She’s coming back.”

“Okay, yes,” I say, “but still. We don’t want to tell anyone, because they might not understand that. They might get the wrong idea.”

“Like that she left us permanently?” There is so much more going on inside that Wrenny-head than I can ever know.

“Maybe, or at least for longer than she was supposed to.” I reach for the handle to the door because I can’t look at her. “Someone might think that.”

“She didn’t, though,” she says. “She’s Mom.”

“Of course she didn’t.” Lie.

“So who cares what anyone thinks?”

“Wren, just don’t, okay?”

“Okay.”

“Some things are private.” I open the door, then lean back across and wipe uselessly at her shirt with my thumb. “Like Mom being on vacation. So, okay?”

“I said okay, okay?” She gets out and waits, stares at me like I’m the most aggravating person on earth. “Hey, Lu?”

“Yeah?” I say, bracing myself for what’s next.

“Your mama’s so fat, she left the house in high heels and came back in flip-flops.”

I would tell her that I hate her new obsession with fat jokes, but I’m not in the mood for any dawdling, so I half laugh and get moving. I want to get inside and quick because there’s also the other thing. And by “other” I mean what makes me sweat just standing here. And by “thing” I mean Digby, who I have known since I was seven but who lately makes a fumbling moronic moron out of me, a full-on halfwit. Ask me my name when I’m in his presence and I’m not likely to be able to tell you. I’d probably just say, “Lllll . . . lllllllu . . .” and you’d have to catch the drool running down my chin.

I know. It’s not at all attractive.

But really. Tall, sweaty, and not wearing a shirt, so the muscles are all right there for the watching. He doesn’t exactly glisten, on account of the fact that he’s whiter than white, that he tans by getting freckles so he’s covered in them now after a whole summer outside. But seeing his hair all plastered to his forehead, his body so long and lean, looping around his dad to get the ball into the hoop, I want to fall out of the car and onto my knees in the driveway, say Lord have mercy, hallelujah, write sonnets and paint him, and worship that one little curve where his neck meets his shoulder that is just so, so perfect.

He is beautiful.

Which is why when he says hi as I pass him, I barely raise a pinky in response. There are two main problems here, aside from the fact that he is Eden’s twin and that’s all kinds of weird.

One, he’s had the same girlfriend since the dawn of time. They’re pinned, she wears his jacket, their marriage certificate is practically already signed. Angels bless their freakin’ union. And two, if I ever did get a chance with him, like if he ever kissed me or something, I would die of implosion. I know I sound like a twelve-year-old mooning over some celebrity, and not the extremely self-possessed woman-tobe that I actually am, but something about him makes me lose my mind. Something about the way he moves, about his himness — it shatters me all the way down. So I hope he never does kiss me. That would be nothing but a disaster. No one needs to see me fall apart like that. Least of all him.

Actually, maybe least of all me.

Eden’s mom, Janie, made meatballs. She doesn’t know how to cook for just four people or even six, since she’s a caterer and party planner, so the fridge is always full of these hors d’oeuvres-ish leftovers. If she’s going to make a dish, she makes a lot of it. You can tell from the smell in the house that the meatballs have been simmering in sauce all day. Meatball essence has found its way into everything.

I watch them for a minute, Eden and Janie. Two redheads, working together over the counter in the big, brandnew open kitchen, backs to us. Everything is just-so here in their dream house, exactly the way they wanted it, so the kitchen somehow looks like an extension of Janie. Eden and her mom look so much alike, except Janie has a more put-together thing than Eden, who is in her ballet getup as she always is outside of school, as though she’s returning to a necessary skin. Janie bumps her butt into Eden’s. Eden bumps back. Butt footsies. Eden is into footsies of all types. They are chopping vegetables for the salad, both stringy and efficient, and together. I put my arm around Wren and pull her into my waist just as Beaver Cleaver, the goldendoodle, jumps on her, and Janie sees us.

“Hi, girls,” she says.

“Hi, Janie,” Wren says, immediately collapsing onto the floor with BC.

I wave.

“It smells really good in here,” Wren says from under white fur. “Are you making vodka sauce?”

Janie smiles. “Vodka sauce? That’s a little advanced, isn’t it?”

“Food Network,” Wren says, jumping to her feet, “and also Gino’s. They have good vodka sauce over there.”

“Well”— Janie points to the cabinet in the dining room, and I start pulling out dishes —“that’s very impressive, Wren.

No, this is not a vodka sauce. It’s plain old marinara, but hopefully you’ll like it.”

“Oh yeah,” Wren says. “I will like it. We’ve been eating frozen pizza for weeks.”

“Have not,” I say. That really is a gross exaggeration.

“Yeah, everything Lucille makes is from a box.”

We had a lot of pizza in the freezer.

“What about your mom?” Janie says. “She’s not bad in the kitchen.”

“She’s not here,” Wren says, then looks at me with a what-am-I-supposed-to-say shrug. “’Cause she’s on vacation,” she adds.

“Oh, right,” Janie says. Her face pinches.

“Maybe you want to watch some TV until dinner?” Eden says, wedging between Janie and Wren.

“Ten minutes,” Janie says, turning back to the kitchen a bit reluctantly. “Finish setting the table, girls.” It feels good to take orders.

“You know,” Eden says, “there is something really messed up and sexist about the fact that we are all in here cooking and acting like domesticated livestock while the boys are outside playing basketball.”

“Oh, for god’s sake, Eden,” Janie says as she pours dressing into the big wooden salad bowl. “I love to cook.”

“His royal highness could at least set the table.” Glasses clink.

“I thought he could use a little time with your dad.”

“Yes, he could. Setting the table. Doing something besides displaying his Neanderthal abilities. You’re encouraging and perpetuating male privilege, you know.”

“Eden, I’m making dinner for my family, which is a joy for me.” She emits a giant sigh. “I shouldn’t have to defend it. And it’s no crime to let them play every once in a while.”

“Yeah, but when do we get to play, Mom? That’s my question.”

My eyes fill. My breath gets weird. They’re so stupid, arguing over this. They don’t know. They don’t know.

“Lucille,” Janie says over Eden’s head, “would you do me a favor and grab the boys? Tell them dinner is about ready.”

Drat.

How does a person go from being like a decorative component in the house that is your life — a nice table, perhaps — to being the pipes, the foundation, the center beam without which the entire structure falls apart? How does a barely noticeable star become your very own sun?

How is it that one day Digby was Eden’s admittedly extra-cute brother, and then the next he stole air, gave jitters, twisted my insides all up? Is this hormones? A glitch in the matrix? A product of internal desperation and my lack of developed self?

I have tried a million times to puzzle out the moment he turned so vital, and I can’t do it. I only know that my stupid, annoying feelings have completely compromised my ability to function around him, that I want to close the space between us and wrap myself around him. My whole being would exhale, I think. It’s ridiculous.

Which is why I stare at my plate. So hard I stare at my plate. I eat my meatball (I can only seem to stomach one), while Eden and Digby throw one-liners at each other. Nobody notices much, and I am afraid to look up, because Digby is exactly across the table from me.

Wren stuffs meatballs all in her face. Sauce drips down the front of her shirt.

“Oh my gosh,” she says to Janie, “you’re, like, a culinary genius.”

Janie beams in my peripheral vision.

“You come here anytime you want,” she says. “You are officially my favorite guest.” She spears some asparagus, smiles, and says, “Culinary.” Shakes her head. “So, Lucille, how long is your mother out of town for?”

Forever. “She should be back in the next couple of days.”

“Is she doing okay?” Since, she wants to say. After. Janie looks so intense all the time.

Wren tilts her head toward me, and I unfreeze.

“You’re doing all right by yourselves down there?” Janie presses.

“Oh, totally,” I say, going in for some asparagus myself. “Mom will be back.”

It all stops. The movement at the table.

“Of course,” Janie says. Her fork tic-tic-tics against the plate. “Obviously she’s coming back.” She takes a bite and chews. “I’ve left a couple of messages for her, you know. Just checking to see if she needs some help. She hasn’t returned my calls.” Straight to voice mail. Yeah, I know all about it. “She must really be enjoying her time away. She must need it.” There’s something in her tone that doesn’t register on her face.

I make myself meet her eyes. Nod. Present a meek smile. On the way back to my plate, those traitorous jellies that live in my head rest on Digby’s, and roller-coaster rush number 892 thrashes through me. He drops his eyes, twists spaghetti, and pays really close attention to his mom and what she is now saying about the wedding she is catering this weekend.

I thud, kick Eden under the table. Mean footsies.

He knows about my mother.

Digby knows.

“All things truly wicked begin from an innocence,” Eden says.

Janie has Wren making some kind of cookie thing, so we are in Eden’s room after dinner, and she is stretching and bending in a way that makes me uncomfortable because those are things the human body shouldn’t do. Also, her feet are disgusting, and I have to look away when she pokes one of them in my face, not on purpose but because she is in the midst of some bananas contortionist move.

“Sick,” I say to a bunion, to a ripped purple nail, to a bloody flap of skin.

“Hemingway,” she says, and flutter, flutter, flutter goes the foot.

“Seriously, you need to do something about that. It looks infected.”

“Baloney,” she says. “Are you listening to me?”

“Hemingway,” I say, wondering how this will ever help me in my life.

“Nobody means to be a douchebag, much less wicked.”

“Serial killers?”

“Even them, I bet. Personality disorders complicate my theory, but you have to figure even they were cute little babies once upon a time. They can’t help it that they got the raw end of the human gene stick. Compassion,” she says.

“You called her a bitch.”

“That’s what I’m saying.”

“That my mother is wicked?” Sometimes I wish she would just spit it out instead of making me work so hard.

“No. That she’s not. That her behavior is. That it stems from innocence . . .”

“But she’s still a douchebag.”

“And a bitch.”

“Nice,” I say, like it’s not nice, which it’s not.

“But I still have compassion for her. It can’t be easy. But now for you,” she says.

“For me.” Numbers start dancing in my head.

I stare at the ceiling, the spot over where Eden sleeps.

“BEWARE, GENTLE KNIGHT” reads the piece of paper taped

across the ceiling. “THERE IS NO GREATER MONSTER THAN REASON.”

“Believe it,” she says, pointing up with a particularly nasty toe.

“I have to pee,” I say.

“McCarthy,” she says, as I make my escape.

Into Digby, who is going down the hall in the opposite direction, wet, with a clean T-shirt and shorts on, which feels weirdly intimate. He was recently in the nude.

He reaches for me. His hand moves from his side, where it was just dangling, not doing much of anything. Now it is awake and touching. It traces my shoulder, skips down my arm, slides across my hand. And then he’s gone. He keeps walking. He never even looked at me.

I fall into a family portrait. I’m surprised that the earthquake inside me doesn’t bring the entire wall of pictures tumbling down. My skin burns. All the blood in my body charges for the spots he touched.

A war.

A fight to the death.

Sometimes, I think as I wander into the steamy bathroom like a half-cocked zombie, something slow happens fast and you can’t quite grasp the moment, whether it was an important one, whether it actually happened or you made it up. It’s already like that. Did he really do that? Did he really run his hand across me like that? Did he? Was he taking liberties? And oh snap, double snap, if this is what happens to me from one tiny finger, then take what I said before about the should-not-ever-kiss thing and times it by about a jillion.

There is a scar now on my arm, where he touched me. It forms on my skin, watery blue, shimmery sort of, like how burns get shiny sometimes, after. How the burnt skin is new at the same time as it’s forever damaged.

I am dramatic.

Flush. Wash. Wander.

Eden.

“What the hell is wrong with you?” she says, petting BC, who has flopped himself onto her bed and is lying across her lap, panting.

I give her a look.

“Are you high? Did you fall into a K-hole while you were gone?”

What if Digby can hear her from wherever he is?

“Cookies!” Wren calls from the kitchen. She sounds delighted.

When we have reconvened around the table and are scarfing down chocolate-chip-oatmeal cookies (except Eden, who would never), Digby slips by. He still doesn’t look at me. There is no secret connection. He grabs the ball by the door, nods in the general direction of the table, and is gone.

It’s four o’clock in the morning. My belly is digesting a single meatball, too much bubbly water, and several cookies. Obviously, I am having trouble sleeping.

In my right hand I hold a pile of paper. Within these many folds of paper are numbers. Bills. Electric. Oil. Car insurance. Now quarterly bills that piled in last week. Water. Sanitation. And then there’s the phone. That, too. That one must be paid. If Mom ever does decide to call, it has to be working. We need food, and Wrenny needs new clothes, and me too for that matter, although let’s just call that one a forget- about-it-for-eternity.

My right hand shakes harder.

In my left — yes, my left hand, ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls — I hold a crisp and shiny one-hundred-dollar bill. That is how I know she is still alive. That is what I got in the mail yesterday. That is how I know that somewhere my mother is still walking this earth. She didn’t get hit in the head. She doesn’t have amnesia. She isn’t dead in a gutter somewhere. She is simply not here. She is somewhere else. One hundred dollars that came in an envelope with no return address and a postmark so I know it came from California. She must be there with long-lost friends, maybe rediscovering her past or something. A note: I’m trying. Love you, Mom. That’s it. That’s all she wrote, folks.

What does it mean? She’s trying to get back to us? Trying to get better? Trying to get a job? Maybe it’s just her way of keeping us from sending the FBI out to look for her. Effective tactic. I wish my last memories of her were of someone I recognized, someone whose behavior I could predict. It kind of makes me want to tower over her with my hands on my hips and tell her that trying is just not good enough, young lady.

Yeah, Mom. I’m trying too.

I trail the bill across my field of vision, let it tickle at my eyelashes. There was a time when a one-hundred-dollar bill would have been the most exciting thing, the promise of a free-for-all at the toy store, something to be tucked away for an indulgent moment.

Not now. Now it’s part of a great big equation that adds up to me being totally screwed. I know she meant to come back. She didn’t leave me the bank card or checks or anything that I’ve been able to find. She would have left me something if she thought she was going forever. She is not wicked, or at least she didn’t start out that way. Still, she isn’t here, and I don’t have what I need to do this job. All she left me was her car and this house.

And Wren.

My left hand is a fist.